Geothermal Heat

Below the surface of the earth is a vast energy source in the form of heat. While far smaller in magnitude than the energy coming from the sun, the available energy within a few kilometers of the surface is higher than current global human consumption. This energy source is partially renewable since convection in the earth’s crust causes heat from the earth’s core to continue rising over time. Roughly half of this energy is “primordial” heat from the earth’s formation that is not renewable, and the other half is produced through radioactive decay of elements in the crust and core of the earth.

There are two basic ways to use this energy:

Geothermal heat: Use electricity to power a heat pump that moves the heat to the surface, where it can be used for heating buildings and low-heat industrial applications.

Geothermal power: Use heat to produce electricity by producing steam that powers a turbine.

I will focus this article on geothermal heat, and come back to geothermal power in the next post. Since geothermal power also relies on heat, much of the background material here will be applicable for both. Also a disclaimer that this is an extremely complex topic and I will be glossing over the details of geology in many places, while relying on credible references to ensure high level accuracy.

The Thermal Gradient

The deeper you go under the earth, the hotter it gets. This variation with depth is known as a thermal gradient. On average, the earth gets hotter at a rate of 20-30 ℃ per km of depth, although this varies greatly depending on the composition of the earth at any particular location. Below 10-20 m, this temperature is largely unaffected by the air temperature at the surface, which means it is stable regardless of seasons. Since a heat pump can extract heat from even low temperature surroundings, this means you don’t necessarily need to dig very deep to extract the heat required for heating small buildings.

The thermal gradient varies with geography, since the thickness of the earth’s crust is not uniform, and plate boundaries, volcanic hotspots, and rock composition all affect this gradient. Generally speaking, it is more attractive to build geothermal resources in locations with a higher thermal gradient, since less drilling depth is required.

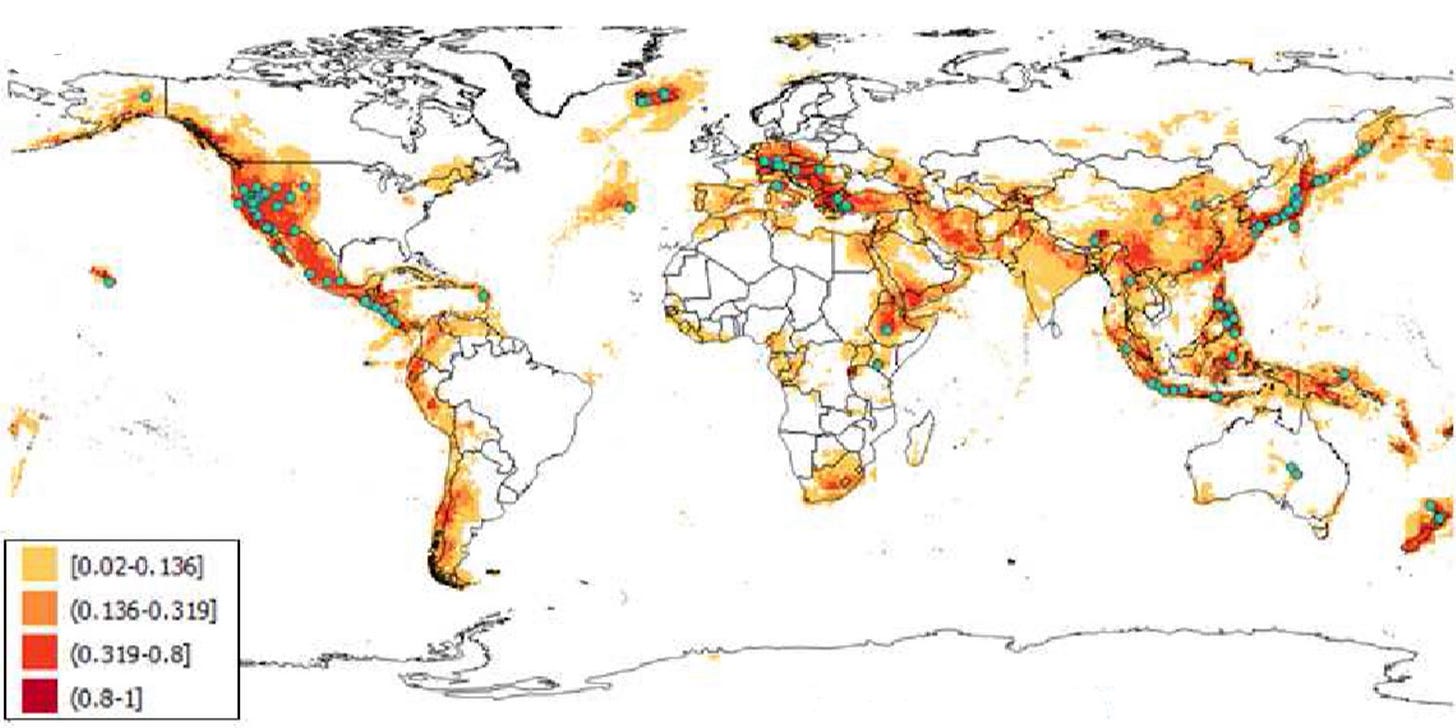

A predictive model of optimal geothermal locations (Journal of Cleaner Production, v. 267).

An interactive map of the world’s thermal gradient and heat flow is available at heatflow.org. Generally speaking, there is an attractive thermal gradient for large scale geothermal systems down the west coast of the Americas, central Europe, and the Pacific coast of Asia.

Heat Flow

Another key fact to understand is that heat moves extremely slowly through rock, in the absence of a fluid such as air or water to transfer it. This thermal conductivity is a function of the temperature, so conductivity is lower near the surface. As an order of magnitude approximation, heat dissipates in sub-surface rock at a rate of 1 µm2 per second, or 0.086 m2 per day. Specific rates depend on many variables such as the type of rock and the specific temperature (for a very detailed specific example, see pages 3-4 of this report from the British Geological Survey). Often thermal conductivity and the thermal gradient are combined in an overall metric called heat flow.

This very low heat flow has major implications for geothermal projects. It means that if you extract a large amount of heat from a location, it can take decades for it to return to its original temperature. Therefore a very large surface area of rock needs to be available to create larger scale geothermal plants, and extraction carefully calibrated to remove heat at a pace that can be sustained over decades. For building heating applications, this can be mitigated by transferring heat in the opposite direction during the summer as part of an air conditioning system. In this case the earth acts as a giant heat battery, which is charged in summer and discharged in winter. This is known as Seasonal Thermal Energy Storage (STES), and is beginning to see adoption in some geothermal projects in Europe.

The Geothermal Recipe

With these basic principles in hand, we can see there are three key ingredients required for any geothermal project:

Hot rocks

An energy carrier (usually water) to carry the heat from the rocks to the surface

Permeability to enable a large surface area of rock to come in contact with water.

Most geothermal systems designed for heating are closed-loop systems. This means a continuous water pipe runs from the surface, down and across the heat source, and back to the surface again. Since heat rises naturally, such systems require minimal pumping power once they are started, due to the thermosiphon effect. To maximize surface area, these systems typically involve many coils or grids of pipes laid either horizontally or vertically. A less common variant is to place coils deep in a natural body of water such as a lake, which is much more efficient since heat flow is much higher in water so it can be extracted sustainably at a faster rate.

In contrast, open-loop systems pump water from an underground aquifer, extract the heat, and then dump the water back again. This is relatively rare for geothermal heating, due to either lack of an appropriate aquifer, or the risk of contaminating or depleting groundwater reserves. Open-loop systems are more common in geothermal electricity generation, but we’ll cover this in the next post.

Economics

Geothermal heating systems largely compete with gas furnaces, or air-source heat pumps. They have far higher upfront costs due to the cost of drilling or digging to lay down the heating loop, but then far lower operating costs than the alternatives once built. The thermosiphon effect reduces the electricity operating costs compared to air source heat pumps, with air source systems being 200-400% efficiency, and ground source systems ranging from 300-600% efficiency (3-6 units of heat energy for each unit of electric energy used to extract it). The ground loop of a geothermal system can operate for 50+ years, which makes it more attractive over a longer time period.

It is difficult to clearly say whether geothermal heating is competitive with air-source heat pumps. For a detached residential home in North America, air-source is largely winning out, since it could take decades to recoup the additional cost of a geothermal system. The low cost of natural gas in North America also makes heat pumps uncompetitive without subsidies or carbon pricing. It is likely more competitive in very cold climates (regularly <-20 ℃) where air-source systems need to be backed up with alternative heating for cold days. For larger scale installations, such as large buildings or district heating, geothermal heating is more attractive, particularly if the geology is favourable (high thermal gradient, and/or large deep aquifers). A prominent example is Paris, which uses a large-scale open-loop heating system to provide heating to a large number of homes (read more). Geothermal heating is also a clear winner in regions with exceptionally favourable geology, such as Iceland, the East African rift, and the “ring of fire” that encircles the Pacific Ocean.

Overall, I expect geothermal heating will remain a relatively small source of energy in most countries. The technology has been around for many decades, and it is difficult to foresee an innovation or scaling breakthrough that will make it a clear winner against the alternatives for residential and other small buildings. Most of the hype around geothermal is currently focused on generating electricity from geothermal, which is a very different scale of system with quite different characteristics. Such systems also produce a significant amount of waste heat, so co-generation of electricity and heat is a promising intersection. I’ll dig into geothermal power in next week’s post.

Resources

Earth’s Interior Heat - free geology textbook chapter with a detailed overview of the earth’s heat.

Energy from and to the Earth - A good overview of both the earth’s heat and the key methods of extracting it.

Geothermal Basics - A primer from the US Department of Energy (still fairly balanced summary from what I can tell)

Thank you, John, for the excellent explanations, here and in the other articles! TIL that the geothermal power system (for heating) that exists close to where I live is an open loop system, and more of an exception rather than something that would work elsewhere. Good to know!